The story of The Scheepvaarthuis

The house with the Golden Windows

With its turrets, sculptures, and Amsterdam School architectural style, the Scheepvaarthuis immediately stands out on the Prins Hendrikkade. Yet, it's not just the exterior that is remarkable. Behind the golden windows lies a story of seafarers, progressive architects, near-decay, and a rebirth as a five-star hotel. Those who step into the Grand Hotel Amrâth Amsterdam step into a piece of Dutch history.

How it all began

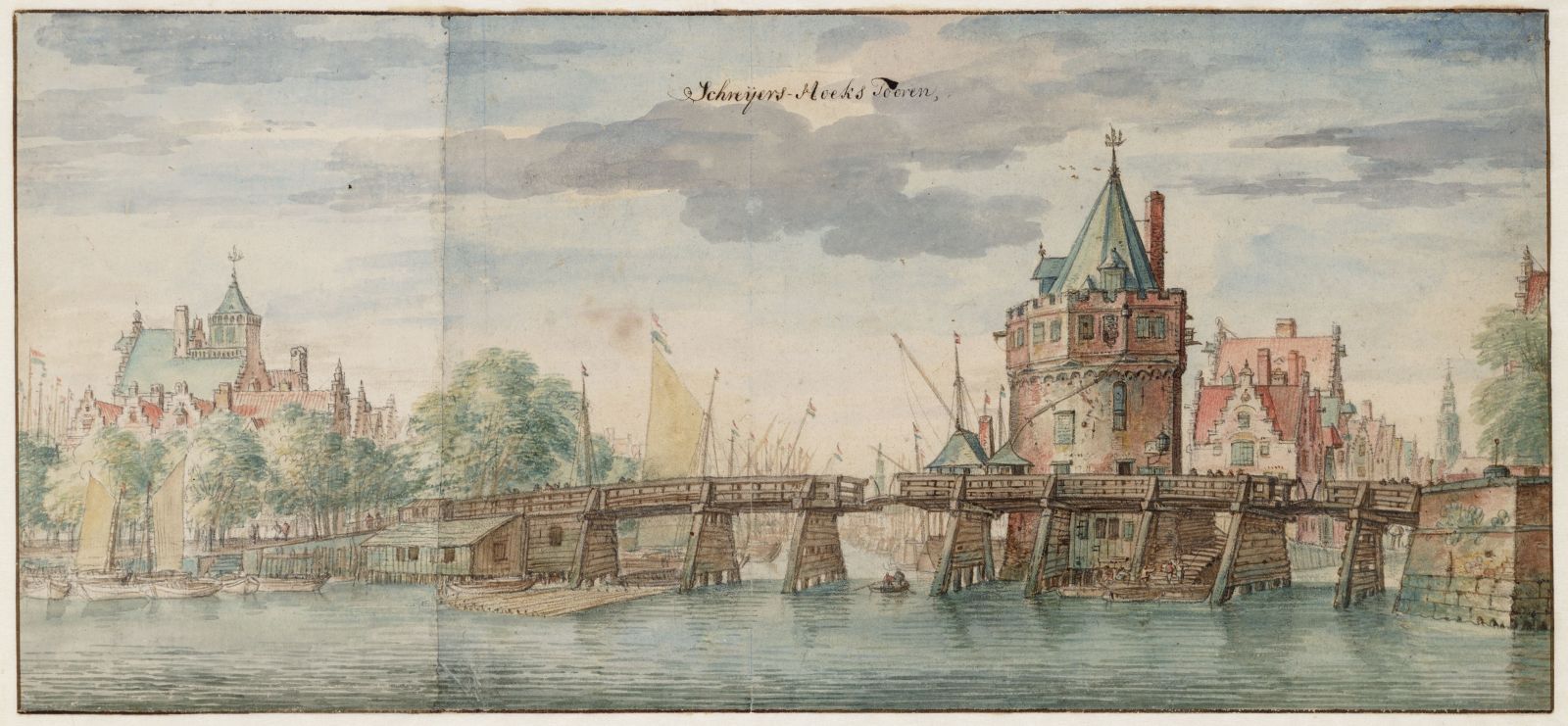

The Scheepvaarthuis is built on a historic site. The story goes that explorer Cornelis de Houtman began his great journey to the East Indies here in 1595. Prints from the first half of the 17th century clearly show the activity in the Amsterdam harbor: rows of masts and sails along the Geldersekade, ships coming and going, and the main bridge connecting the Schreierstoren with what is now the Prins Hendrikkade. Approximately at the height of the houses that rise above the trees stands the Scheepvaarthuis today.

For centuries, this has been a place of departure. A logical location, therefore, when in the early 20th century, six shipping companies decide to join forces in a joint headquarters.

| Schreierstoren, ca 1620 - 1640 | Maker unknown | Amsterdam City Archives |

A mighty figurehead on the quay

In the early 20th century, six shipping companies decide to join forces in a joint headquarters. Here, tickets for sea voyages to, among others, the Dutch East Indies and Africa will be sold. The Prins Hendrikkade is an excellent and historic location near the Eastern Docklands where ships arrive and depart and where many seafarers began their journeys.

At that time, faith in shipping is unwavering. Whoever controls the sea controls trade. The intended building must reflect that: grandeur, power, and ambition. In 1911, the young architect Johan Melchior van der Meij is commissioned to design this mighty figurehead. He is a promising talent, winner of the Prix de Rome, and decides to fulfill the commission as a Gesamtkunstwerk: a total work in which architecture, art, and craftsmanship form one whole. He enlists the help of colleagues like Piet Kramer and Michel de Klerk, who together with him build what will later be known as the Amsterdam School.

A bold design in a new style

The architects are children of their time, but also rebels. In the 19th century, neo-styles are popular: buildings in neo-Renaissance style or neo-Gothic, with stepped gables, columns, and arches. They fit nicely into the streetscape, but they are not innovative.

Van der Meij looks further. In Belgium and France, a new movement arises, called Art Nouveau, known as Jugendstil in Germany and Austria. The Amsterdam School can be seen as the Dutch version of that: natural forms, graceful decorations, and a clear distance from the harsh, mechanical world of factories and machines. Nature and the sea become important sources of inspiration. The forms Van der Meij chooses have not been seen in buildings before. Executing such a prestigious commission in a style that has yet to be invented requires courage. But that is precisely what makes the Scheepvaarthuis unique.

| Loading and unloading inland vessel at the Open Harbor Front, ca 1930 | Maker unknown | Amsterdam City Archives |

The exterior: a facade full of stories

For the construction of the building, Van der Meij chooses a concrete skeleton, very modern at the time. Because the walls no longer need to bear the weight, there is room for rich decoration. He uses over two hundred different types of stones for the facade. An exceptional amount, even at that time.

Renowned sculptors such as Van den Eijnde and Krop were closely involved in the creation of the building’s sculptural work. Van den Eijnde led the sculpture studio responsible for producing the pieces for the Scheepvaarthuis, with Krop acting as his right-hand man. Sculptor Van Lunteren also contributed, creating the innovative plinth decorations, including the intertwined fish motifs crafted using the then modern pneumatic hammer. Next to the main entrance, mythical figures depict the four world seas. On the facade, 29 heads of seafarers and explorers look over the city. Those who take the time discover more and more: dates, anchors, sea creatures, constellations, wave motifs, trade goods, and ship lanterns.

The ironwork also tells a story. In the bars in front of the shop windows, anchors and tridents are incorporated, in the railing along the facade waves and the letters SH: ScheepvaartHuis. The roof is finished with lead in which ship knots are applied, and covered with slate from Wales. Above the entrance, the lead figures Poseidon and Fortuna, the god of the sea and the goddess of fortune, watch as symbols of the maritime success the shipping companies strive for. That all this is realized between 1913 and 1916 is impressive.

.png)

| Plumber at work on the roof, ca 1915, 1916 | Bernard Eilers | Amsterdam City Archives |

The Interior: the world in glass, wood and textile

Inside, the line from outside continues seamlessly. The unity between facade and interior is characteristic of Art Nouveau and the Amsterdam School, and Van der Meij guards that strictly. A team of young artists works out the maritime themes down to the smallest details.

In the heart of the building is the large stained-glass dome by Willem Bogtman, a canopy of 106 m² showing the world map with shipping routes, whales, ships, and the zodiac. The Beraadzaal is designed by Nieuwenhuis and is executed down to the last detail: wall coverings with seahorses and natural motifs, carpets full of fish and wave movements, dark wood that gives the space intimacy. It is the largest intact design by Nieuwenhuis.

.png)

Each of the directors’ rooms received its own distinctive character. Under the leadership of Van der Meij, who oversaw all designs and contributed to them himself, Kramer, De Klerk and Nieuwenhuis created unique interiors featuring elegant woodcarving and recurring maritime motifs. Van der Meij defined the framework within which each designer worked and bore final responsibility towards the six commissioning shipping companies. This characteristic style later found its way on board the vessels as well, where ship interiors were designed in the same spirit.

.png)

Upon completion, the Scheepvaarthuis is also hypermodern. There is central heating according to the latest techniques, recognizable by the wall grilles on each floor. The roof terrace is intended to allow staff to lunch outside, a progressive idea. The paternoster lift, which can transport many more people than a regular lift, is used intensively. It requires good timing and is therefore less suitable for hotel guests, but it still works.

Glory, competition and vacancy

In 1916, the six shipping companies have their prestigious headquarters. Travelers book their journeys to distant lands in an atmosphere of luxury and progress. The Dutch East Indies and Africa are popular, but there are also connections from Java to New York, China, Japan, and South America. Both passengers and freight clients conduct their business in the Scheepvaarthuis. The counters in the hall still remind us of this; the earned money is safely stored in the vault in the basement.

After World War II, the playing field changes. The Netherlands loses the Dutch East Indies, shipping companies are nationalized, aviation rises, and the port of Rotterdam develops into the most important container port. Amsterdam misses that opportunity. Mergers follow, and eventually, the last companies move to Rotterdam. In 1972, the Scheepvaarthuis becomes a national monument.

The municipality buys the building, and in 1983 the GVB moves in. The interior is adapted according to the fashion of that time, with pastel-colored ceiling tiles, computer floors, and fluorescent lighting. Many Amsterdammers know the Scheepvaarthuis from this period mainly as the place where you could pay off your wheel clamp. The grandeur of the past is largely hidden from view, but not gone.

From office to Grand Hotel

In 1998, the municipality decides to sell the building. Real estate entrepreneur Van Eijl is the only bidder and becomes the new owner. He sees what the building can be: a characteristic and artistic five-star hotel, with its own identity and a timeless appearance. Not a trendy boutique hotel that follows fashion, but a grand hotel that feels like it has always been there. Architect Ray Kentie receives the challenging task of making that happen.

During the renovation, the exterior is tackled first. Under a thick layer of soot, the facade turns out to be much lighter than expected. After a thorough cleaning, the original brick emerges: a rich palette of light yellow tones to orange ochers. The window frames also undergo a transformation. After removing many layers of paint, the original Javanese teak wood emerges. Only by varnishing it does the building gain a warm, radiant appearance and live up to its nickname again: the house with the golden windows.

The ironwork and the wrought iron along the facade are in poor condition. It requires craftsmanship to restore the artistic wrought iron, but eventually, two blacksmiths take on the task. When the elegant letters "Het Scheepvaarthuis" on the central part of the facade are re-gilded, the building is already much more beautiful than it has been in years.

Reconstruction, art and craftsmanship

In 2003, an intensive demolition and renovation phase begins. Over 12,000 m² of suspended ceilings, 3,000 m² of computer flooring, and thousands of fluorescent tubes are removed. Once the building is stripped of all later additions, it becomes clear how special the original design still is.

Kentie chooses to preserve as many original elements as possible: walls, doors, frames, paneling, ceilings, staircases, lighting, and furniture. The warm honey-yellow color of the frames outside is continued in furniture and paneling inside. The large glass dome is cleaned and once again allows abundant daylight to flood the hall. The vault in the basement gets a new life as a wine cellar. For wallpaper and curtains, Kentie uses enlarged patterns of historical wall coverings by Nieuwenhuis.

Some questions are complex, such as: how do you place a bathroom in a monumental director's room without affecting the wood-carved walls? The solution is found in glass modules that are placed freely in the rooms. This way, the monumental interior remains intact, and the space still gains modern comfort.

At the entrance of the restaurant stands "Il Canto delle Sirene," a sculpture by the Italian sculptor Luigi Galligani, inspired by the Odyssey. Other contemporary artists are also involved, in the spirit of the original Gesamtkunstwerk. Gerti Bierenbroodspot designs lithographs of shells, fish, and sea monsters, the hand-painted tiles on the bottom of the pool, and the porcelain tableware. Christie van der Haak is responsible for upholstery in rooms and public spaces, with patterns that hark back to the elegant style of Nieuwenhuis.

.png)

The purchase of the building also includes much original furniture. Chairs, desks, and cabinets feature maritime details: a backrest in the shape of Neptune's trident, an owl hidden in a border, the triple Andreas cross as a nod to Amsterdam. A curator carefully inventories everything, and the collection is supplemented with furniture from the same style period. Most of it is simply in the rooms and used by hotel guests.

Opening as Grand Hotel Amrâth Amsterdam and expansion

After a year and a half of demolition and a year of renovation, Grand Hotel Amrâth Amsterdam opens its doors in June 2007, initially with five rooms. By September, there are already a hundred, and almost a year later, all 165 rooms are available. Behind the historic facade lies an extremely comfortable and luxurious hotel, with renewed plumbing, advanced climate control, a swimming pool, and an environmentally friendly heat-cold installation. Guests appreciate the authentic and historical environment in which they stay and leave rave reviews. The hotel receives multiple awards and can rightfully call itself "a world of luxury and art."

In 2016, the Scheepvaarthuis is further expanded. On the undeveloped courtyard, a new wing with forty rooms and an underground parking garage rises. The facade subtly refers to the Amsterdam canal houses across the Buiten Bantammerstraat. This expansion is also designed by Ray Kentie and Partners. The new rooms are furnished with style details from the Amsterdam School, complete with replicas of original furniture, wall coverings, and carpeting. In April 2018, this part of the hotel is festively opened with the unveiling of a new stained-glass ceiling in restaurant Seven Seas, designed by Christie van der Haak.

A living house with Golden Windows

Today, the Scheepvaarthuis is a living monument: once a departure point for seafarers, then a mighty headquarters, later a GVB building, and now a five-star hotel where history, art, and hospitality come together. The rich history is felt in every detail, in the stained-glass dome, the marble stairs, the sculptures on the facade, and the warm light that falls through the golden windows.

Grand Hotel Amrâth Amsterdam is therefore not just a hotel, but a house with a story. A house with golden windows, built on a piece of Amsterdam history that still lives on every day.

.png)